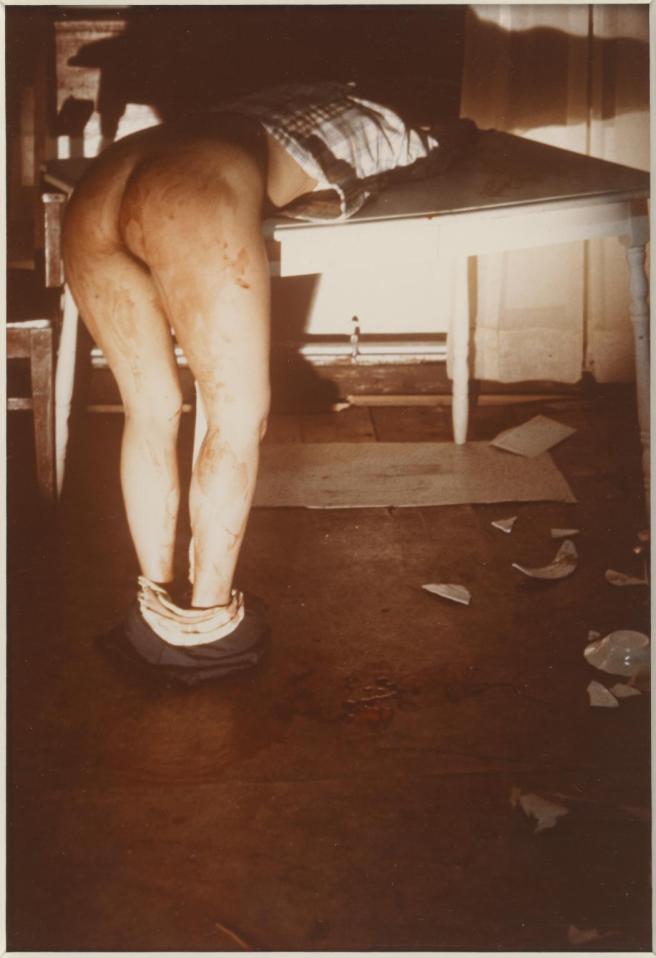

Rape scene

Image from a scene where Mendieta posed in the vulnerable and explicit position in response to a highly publicised rape and murder of a nurse. ‘A personal response to the situation’ – the violent act frightened her and she reacted by reenacting a brutal scene signifying violence against women.

Untitled (Rape Scene) is the first and most significant of three works Mendieta created in response to the murder incident. In two further actions she was photographed lying semi-naked and spattered with blood in various outdoor locations on the perimeters of the University campus.

More photographs of her consisted of her lying in what appears to be a pool of blood as if she were the victim of an accident or crime, while a fellow student stood over her taking a photo – in reference to the press.

Another series consisted of photos of people looking at a pile of blood on the side of a street. Documenting reactions

Mendieta – death of a chicken. Recreation of Viennese actions work. She created her own version of their ritualistic and cathartic actions.

‘Her identification with the sacrificial victim staged in many of these works, and to which Untitled (Rape Scene) relates, stems in part from her sense of loss as a result of having been dislocated from her family and home in Cuba and sent into exile in the US with her sister in 1961 as a result of the political upheavals there.’

In all her feathered performances of 1974, Mendieta transforms herself into the sacrificial victim – the creature that must be killed in order to produce new life. Blood is central to rituals of the Catholic Church, the religion in which Mendieta was raised, through the metaphor of wine.

Mendieta plays with vision and surface in these early works, she also explores physical and material transformations through body-based works. With a matter-of-fact, almost documentary aesthetic, “Sweating Blood” (1973) is a single shot of Mendieta’s head, eyes closed and unflinching, as blood slowly beings to trickle from her scalp. Without any sense of violence, “Sweating Blood” dramatizes the process of thought as a physiological experience. Blood is also the medium of artistic process in “Untitled (Blood Sign #2/Body Tracks)” (1979), a silent film projected directly onto a bare white wall of a woman in front of a bare white wall, her back to the camera, her body pressed into the wall, arms raised in a “V” above her head. As the film rolls, she slowly sinks to her knees, dragging her arms on the wall, leaving blood red tracks in their wake. Her ghostly image is seamlessly integrated into the gallery space, a haunting reminder of the presence of her body as integral to the performance. Accompanying the film are the paper and blood remains of Mendieta’s Body Tracks project, reminiscent of Yves Klein’s Anthropometries, but fragmentary and marked not with the artist’s signature color, but instead with the literal material of her body. Mendieta’s use of blood in her performances and in drawings, photographs, and films has been connected to Hermann Nitsch and the Vienna Actionists, who were well known among the students at Intermedia, but although Body Tracks shares a ritualistic character with the work of the Actionists, the encounter is between the artist and her own body and materials; it is visceral, not violent.

But violence also fascinated Mendieta. The dark scene in an 8×10 color photograph dated 1973 offers an almost matter-of-fact crime scene image: harsh spotlight illuminates an impoverished apartment with broken dishes on the floor and a decrepit wooden table, with the artist’s body bent at a right angle away from the camera, ass in the air, covered in blood dripping down her bare legs and pooling in the white panties around her ankles, head invisible in the shadows. “Untitled (Rape Scene)” (1973) is the record of a performance/ installation Mendieta created in her apartment in Iowa to recreate the scene of a real violent rape-murder of a young woman that March that had been reported in detail in the press. Although the image immediately suggests a feminist politics, a statement against violence against women, when coupled with the series of slides shown in a vitrine nearby of Untitled (People Looking at Blood, Moffit) (1973), rows of mundane street shots of ordinary passersby in front of a doorway where Mendieta spread animal blood, the effect is not a condemnation of violence, but a sense of detachment and displacement. The absence of causality in these images, the implication of violence but never its depiction, works to displace the viewer’s ability to comprehend each scene as a narrative; rather the images seem to challenge the viewer, to heighten a sense of dislocation, mediating any sense of transparency in Mendieta’s use of her own body in the work. These are images are some of the most tempting to read biographically given the intimate violence that lead to Mendieta’s death, yet it is precisely in these images that the artist refuses that paradigm: her defiant stare in “Untitled (Self-Portrait with Blood)” (1973), bloodied face filling the frame is one of the most powerful in the show.’

She gave up painting, which she felt was “not real enough.” During this time Mendieta also used blood in many works, a medium that is symbolic on multiple levels. On the one hand, it suggests death and violence. On the other hand, blood is a life force. It is visceral and powerful, as suggested by its use in religious rituals, particularly those of Catholicism and Santeria, with which Mendieta was familiar in Cuba. Untitled (Death of a Chicken) (1972) references the latter Afro-Cuban religion. Standing nude and in front of a white wall, Mendieta held a newly decapitated chicken by its feet. As the animal struggled, its blood splashed across the floor and wall, inadvertently creating an Abstract Expressionist–like scenario and artwork. Bird Transformation (1972), another performative piece, involved covering her body in blood and rolling in white feathers to transform herself into a fowl. Blood also figures as that which runs through our veins in the video Sweating Blood (1973), as the fluid appears to drain from Mendieta’s scalp.

Siluetas

Long-term project with over 200 silhouettes in all

She photographed her silhouettes created from the earth over time, documenting their ephemerality and presence via absence. She made a wealth of short films following the same concepts, however also showing the ritual processes of working and becoming part of the earth.

“I have been carrying out a dialogue between the landscape and the female body (based on my own silhouette). I believe this has been a direct result of my having been torn from my homeland (Cuba) during my adolescence. I am overwhelmed by the feeling of having been cast from the womb (nature). My art is the way I re-establish the bonds that unite me to the universe. It is a return to the maternal source. Through my earth/body sculptures I become one with the earth … I become an extension of nature and nature becomes an extension of my body. This obsessive act of reasserting my ties with the earth is really the reactivation of primaeval beliefs … [in] an omnipresent female force, the after-image of being encompassed within the womb.”

Each Silueta involved the immersion of Mendieta’s body with nature, either literally, by lying naked within landscapes, or figuratively, by creating outlines of her body from an array of materials, such as mud, sand, rocks, leaves, grass, flowers, and branches. The works suggest that while bodies demarcate spaces, spaces also define experiences in the world. In a sense, the Siluetas recall Mendieta’s formative years—her removal and relocation to various spaces and her subsequent struggles to fit in or adjust to each of them.

Nonetheless, one should not regard the Siluetas as a meditation on loss or longing entirely. While empathic, that interpretation delimits Mendieta’s identity and the possibilities of how she and others respond to exile, emigration, and other similar circumstances. The Siluetas are spaces from which Mendieta willfully departed. She physically defined her body then stepped away, in a sense liberating herself literally and also figuratively from defined parameters and fixed categories. The works suggest both her absence and presence and imply a desire for and doubt of classifications like gender, ethnicity, sexuality, and nationality, which also change through spaces and societies. Thus, the Siluetas are uncanny spaces that facilitate the confusion, interrogation, and eventual negotiation of meanings.